Office Hours: 30 Minutes with Danitra Blue

Office Hours : Danitra Blue, Director of Remote Learning and Program Director for the US South at High Resolves

First: tell us a little bit about your background as a teacher. What brought you to where you are today?

It’s been a long journey. It starts with an interest in education and a passion for education. Growing up, I had aunts and uncles who were teachers or worked as administrators; my mom is a school bus driver. Aside from being a student, I was always around people who cared about education and service and addressing social issues. Over time, I’d thought I was going to work toward those issues by pursuing a career in law, and then in college I started working for after-school and summer programs that worked with students across Boston. From the moment I taught my first 4th grade summer class, I knew I needed to work in education. Before getting into policy or nonprofit leadership, I felt that I needed to be a classroom teacher first. There are a lot of folks with their hands in education without that experience, and so I wanted to start there.

I applied for Teach For America and was sent to New Orleans. While being a first-year teacher certainly came with its challenges, I’m grateful for that opportunity. I joined City Year New Orleans, partnering with high need schools to lead interventions. Within that role, I managed teams of K-12 educators in two different schools. That role showed me more of a birds’-eye view of challenges that students are facing, support they need with social emotional learning, and what root causes of a low grade or attendance issue are. The experience helped me put pieces together about what solutions schools really need: not just band-aids, but actions to address root causes of those visible issues.

Someone from High Resolves reached out on Linkedin and said they were looking to expand and have someone on the ground in New Orleans. I became the organization’s first staff member here, and I’ve been with High Resolves for a little over three years. Over time, my role has adjusted to meet the needs of our school partners. I began as a Program Director leading our work in New Orleans, then expanded to leading our work across the US South, and now I’m managing that while also serving as our National Director of Remote Learning for the US.

Part of your work at High Resolves involves developing students’ “social skills.” What does that mean to you? How can students’ experiences in classrooms contribute to that growth?

When I think about students’ social skills, I think first about the 7th graders who I used to teach. They’re in the middle of being a child and an adult; middle school is an awkward time. Especially having taught English, which includes teaching skills around how to have effective dialogue, how to respectfully disagree, how to analyze texts and arguments, and how you choose the words you want to use to convey your ideas — these critical skills were part of my curriculum then and are central to my work now. A gap that I see in schools, which is where programs like High Resolves and REAL come in, is that being able to communicate your thoughts related to a text or a historical concept can feel different from relating your thoughts about a social issue or identity or a deeply personal idea. They’re related, but distinct skills. What we’re able to do is give young people and educators some concrete strategies and some practice in building those social skills in order to help address some of humanity’s greatest challenges. In the same way students can analyze a text, they can make a case for why we need to address poverty. There are commonalities that some educators are tapping into, but schools need a more comprehensive solution to make sure that’s happening.

It seems like that’s a tool for motivation and engagement, too.

There are some concepts that lend themselves well to bridging the gap between academic, classroom work and social existence beyond the classroom.. When I taught A Raisin in the Sun, we discussed not only what was going on in that play but how it relates to New Orleans today, especially with housing segregation. The content mirrored. Students were able to see that what’s happening within that text is happening here and now in a different way. I wanted them to develop a voice around both the text and their lives.

What are some key texts and thinkers that you’re engaging right now as you think through your work in instructional and school design?

Before I share recommendations, I’ll say that in my work, when I think about supporting educators or when we’re designing professional development and training for adults, what we focus on is making sure that educators are able to experience some of the same types of complex conversations they want to guide students through. Within High Resolves’ curriculum, one thematic focus involves exploring identity and purpose: areas of focus are unconscious bias, race/racism, microaggressions, gender identity. The general guiding principle for me is that if an educator wants a young person in their classroom to be able to discuss those topics, then educators also need practice discussing those topics. Depending on age or context, a lot of people might not have practice with those complex conversations. The general guiding principle for me is that you should eat your own food if you’re serving it to the students. Address the recipe, get it right.

There are also many great podcasts and texts out there that are definitely helpful and instructive, but for me, that’s the main goal. Even if the process is messy or complicated, theo nly way to do the work is to begin having those unpracticed conversations. Jump in, try to fumble your way through, and learn from it..

Historically, students’ experiences of the classroom is often that discussions that engage questions and issues of identity silence them, even if teachers try to use a social justice lens or engage issues of identity through course materials. Rather than developing content or reading new books, though, it sounds like you’re suggesting practicing this teaching, like a skill.

When educators are discussing topics where there isn’t a clear answer, it can be really difficult to feel like you don’t have to be the keeper of knowledge. Teaching the skill of having conversations about identity is different than teaching the skill of how to apply a math formula to the real world. You can’t apply formulas to an identity. We, as educators, have to be comfortable with fumbling through conversations and not having all the answers and having to model what it’s like when you say the wrong thing or learn something. The dominant culture of a school or society can be working against the change, which is why I love to partner with educators and schools to help them reimagine the ways they serve their schools and communities.

At High Resolves, we have free classroom resources that educators can take, and one of those lessons is called “evaluating experts.” There’s a section that asks students to reflect on what an expert is and how you know. By the end of the lesson, they’ve analyzed people who seem to have authority, like Dr. Oz. There are case studies within that lesson, and by the end students, are questioning whether their teachers are experts or not. Training teachers to facilitate that questioning sometimes leads to a fear that students will find out that their teachers don’t know everything. But that’s okay; I think they should. It’s an important part of being an educator to recognize that you don’t.

You’ve moved, recently, into your role as Director of Remote Learning. What do you prioritize in that role? What are some of the problems and opportunities that you’re focused on when thinking about expanding, implementing, and improving remote learning?

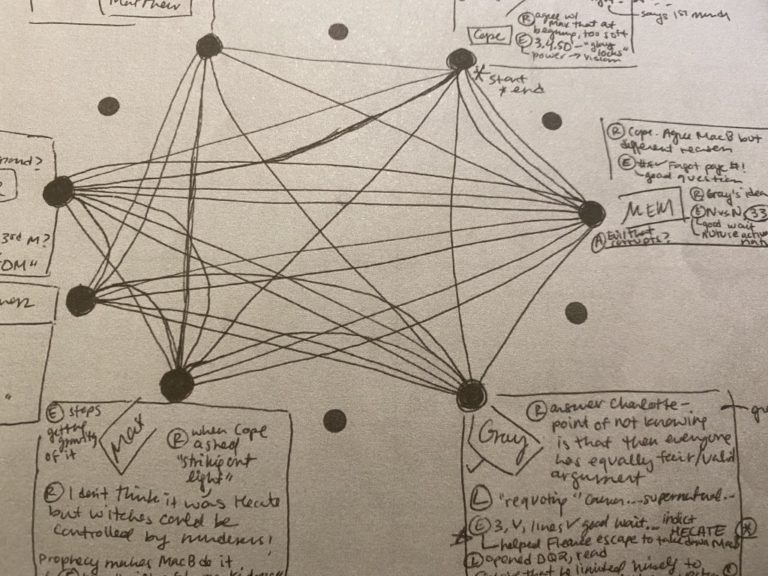

This is my favorite thing to talk about. I think that remote learning is constantly evolving. Before Covid, what came to mind when we thought of online learning was online modules and MasterClass — the usual suspects. You log in, read a lot, type a lot, and you’re done. That’s still a part of it in some spaces, but what we’re trying to do at High Resolves, and what I’m tasked with, is re-imagining and developing our in-person immersive learning experiences, designed from 2-2.5 hours for up to 60 students, with discussion and movement and debate, into an online space. How do you translate that feeling? There’s so much that we’ve learned throughout the pandemic.

Within High Resolves, we developed a partnership with OpenLearning, which is based in Australia, to develop and facilitate online learning experiences using the OpenLearning platform. Thankfully, we were a little ahead of the curve because High Resolves is also based in Australia, and at the time that this partnership was forged, Australia had experienced the effects of COVID before we did in the US. We’ve seen how Covid has played out: life in Australia is almost back to normal, and we are not. As I’m designing or adapting courses, determining where and when and how remote learning is effective, the main piece of information that I’m using to guide is: what are students experiencing right now? What does it seem like they need? How can we still achieve these learning outcomes online?

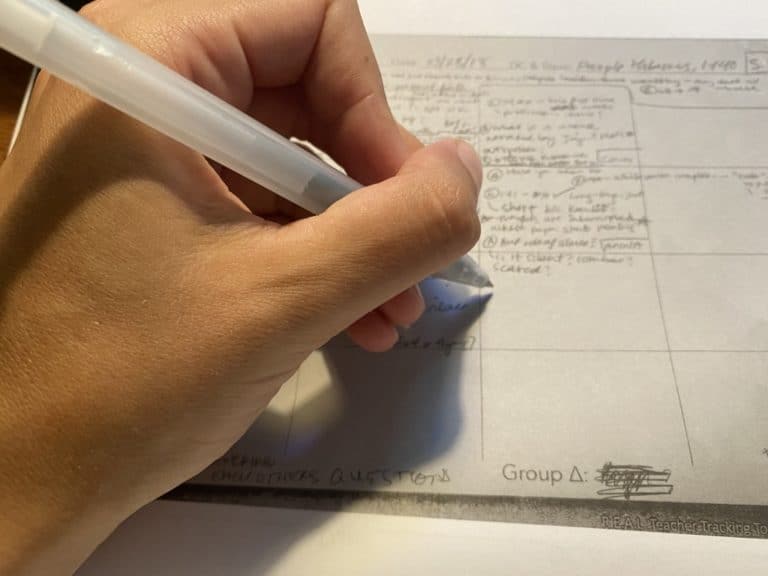

As an example of how we approach remote learning, I’ve recently had the chance to facilitate sessions for two international cohorts of young people. Each cohort was composed of about 30 students from various countries. Students from Chile, Peru, US, Canada, and Jamaica joined together to discuss identity, social justice, morals and ethics. Another group was working on creating Videos for Change — I was guiding them to create a one-minute video about a social issue they’re passionate about. It can be challenging to discuss these huge topics even in person. Then, add the fact that English is for many of the students a second, third, or even fourth language. To address all of these complex needs, I found ways to ask questions clearly and give students multiple ways to engage with the content on Zoom and on the OpenLearning platform that houses our courses. For example, during the session, I would show a question on my screen, and next to the question would be an icon to show students how they could engage. These icons look like a typing icon, a speech bubble, and a thought bubble to indicate just thinking about the question. It’s key to be clear with language and also to use images to show different ways you can engage.

Norm-setting, expectation-setting, and community agreements are also really important in cultivating these discussion spaces. Before discussing identity, we start with: how do we want to talk to each other? What are our expectations? We encourage students to be brave, to be present, and to expect non-closure. Introducing these expectations demonstrated how students should respond to each other during our dialogue, and it led to students sharing other norms that they focus on in their schools and home communities.

Adaptability is also important. With students joining in from various communities, bandwidth is an issue. We had a student who wanted to join so badly that he called in on his phone, outside in the rain, to discuss identity. There were times when I had to adapt the session because of bandwidth, and that’s okay. Being able to adapt shows students that you’re watching and listening.

Educators have had to learn to listen in different ways than we’re used to to hear the places our students are coming from.

OpenLearning, the online platform that houses our content, allows us to see when learners are logging in and to track their progress. It gives us an overwhelming amount of data. In addition to seeing when students are logging in, we can see how much time they spend on specific activities. Are they working at a time that’s most useful to them? Are more students working at 7 am, or 4 pm, or 1 am? Those are things we wouldn’t normally see if a student turns in an assignment on a piece of paper. The ability to access this data serves as a kind of wellness check. You can see if the system you have set up is working for your students or not.

The root causes you were discussing earlier — the deeper sources of the academic distress that teachers see — haven’t changed with the pandemic, but their manifestations and the degree to which we notice them have. It’s been an exhausting year. Where do we go from here? What does the future (or some part of the future) of education look like in the next year? In the next five-ten years?

I wish I knew! I think this time we’ve spent in our homes and figuring out ways to work remotely and learn remotely has forced us to be really reflective. In the past year, and even before, the most interesting conversations I’ve been a part of are about ways to go back to basics: what’s the purpose of education? What’s the purpose of schooling? Are those things the same, do they overlap, or are they separate things? Time is limited for everyone, but especially for educators. I hope that we can still continue to have these conversations about how we want to approach learning. I don’t want us to lose the collaborative spirit that came up when everyone was working to learn new tools and strategies as we figure out how to move back into in-person or remote or hybrid learning.

My greatest hope is that educators continue to listen to their students when they voice what they need. In one of the online workshops I was leading, Videos for Change, I asked students to choose the social issue they care about the most right now, then research it, determine root causes and symptoms, and pick one thing to focus on to try to change someone else’s heart or mind about that social issue through a one minute video. One middle school student created a one minute video about her challenges with mental health and school. She created an animated video that showed images of Google Classroom assignments that were past due, her internet cutting out, noise in the background, and she was communicating how much she and other students needed this approach to stop. I knew that, logically, but to hear a student put that out there through a one minute video was impactful to me. It impacted her teachers, too. At one of the all-staff meetings, they played that student’s video to give that visual to the teachers. As much as we can, we need to continue listening to what our kids are saying.

When I’m trying to imagine the future, I often find it helpful to return to the past. One of the texts that I often return to is James Baldwin’s “A Talk to Teachers.” A lot of it is about racial identity and the responsibility of any educator who is teaching a Black student. The piece is from 1963, but it easily could’ve been written today. There’s a line toward the end about how part of the role of educators is to help students decide what they’re worth. That always sticks out to me. We may not know exactly the purpose of education or be able to agree about the best strategies, but at the end of the day we’re helping young people decide what they’re worth.