Office Hours: Interview with Jini Rae Sparkman

For this week’s Office Hours post, we spoke with Jini Rae Sparkman, Director of the Office of Equity and Inclusion + English Teacher at The Holderness School. Jini offers her insights on the ways and means that we do, can, and should hold conversations at school – and the ways that community-based conversations will change our schools for the better.

It’s great to speak with you, Jini. This is a year in which many more schools and practitioners have acknowledged the relevance and importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion to enact change both in and through their schools.

For DEI+J [Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice] practitioners this year, the ability to reshape conversation about what schools are and could be is something we’ve been waiting for and pushing towards for a long time.

How did you get into equity and inclusion work?

I think my life was always headed in that direction. I grew up in Texas public schools. I went to college to play basketball and volleyball, and then I dropped out. I went back to school in my 30s. By that time, I’d traveled to different places across the country and lived in different situations, and my eyes were opened through those experiences to how small my world had been. Traveling and working in diverse places helped me to understand that we create our realities and that those lived experiences are very different for different people.

I knew that I’d always wanted to be in education and that was true when I went back to school, but I also realized that being an educator is who I am. It is the ethos of my life. I’ve never stopped being a teacher, whether I was working behind a bar or in a gas station somewhere or in front of students or colleagues. I was always trying to help people learn. It felt really good to go back to school and be intentional about the type of learning and impact I hoped to have. I was teaching at Plymouth State in the Women’s Studies and English departments. I loved that place; they mentored me through my bachelor’s and master’s degrees and into my professional life. Still, I wanted more connection with students and colleagues than the higher ed level allowed. Working at the college level, you connect with a few kids, but not a lot of kids. I got to teach a lot of incredible courses. But all the while, I was thinking about how I could find that connection and looking for a next step.

Someone in my office was looking at high school principal jobs and pulled up this job in the English Department at Holderness. When I read about it, I immediately called my wife and said: “If I could design a school to work at, it would be this one.”

In each interview I was in at Holderness, I said: “I want you to know that I teach from a social justice platform.” I didn’t want to teach somewhere that they didn’t want a teacher who would say such a thing. The foundation of my work has always been D, E, and I, and specifically J – justice. This isn’t just a job. It is how I live and who I strive to be. It goes to my philosophy and belief that we create our world. And they hired me. I was brought in to work at the school to coach basketball, teach English, and live in the dorm. But I was that hell-raiser; I’d see things that weren’t okay, and I’d say something. Within my first year on the campus, I was firing emails to all the deans at once when I noticed inequities and opportunities to make a more just community. I lived what I said. For me, that’s what it’s always been about. But I also had a lot to learn. I made mistakes and was so fortunate to have excellent mentors to guide me and a community of adults who truly care. Two years into my work at Holderness, we’d had a diversity coordinator, but after that person moved on, the school evolved that role to an Equity and Inclusion office. I stepped into my current role then.

DEI+J isn’t just what I do; it’s integral to who I am – and that is why I love teaching, too. I have 9th grade English now. The reason I love high school is because this is when kids start to rebel, and you need someone who’s going to antagonize and push back. Give me the years when they won’t accept what I say! So that they can take ownership of what they learn and grow from there. I still teach and coach. Boarding school offers these moments when, 10:00 at night, girls come into the common room to talk about love or our world or their lives. They’re so curious, and they want to know you because they don’t quite know themselves yet. That’s a really important part of this. So much of the work we need to do to build the world is founded on those relationships, and teaching allows us to do this, particularly when we understand teaching as so much more than what happens in classrooms.

How has the field changed in your time?

DEI+J work isn’t something you do — it has to be the lens through which everything in your school passes. At independent schools like mine, especially, internalized white supremacy as a system is all around, as well as and the white savior role that so often shows up in independent schools. We made it about diversity first (this was a national trend), but that focused on just making places have more non-white people. It was focused on this idea of “helping out.” People talk about “they and them,” which shows that there’s hierarchy of social power between those who are in and those who are out, and you hear that a lot. Schools were trying to bring in young people from BIPOC communities, but then those students would struggle to find success in independent schools. I saw this quote on Instagram yesterday about how diversifying schools is just another term for desegregation; population numbers don’t mean change. So often it is and has been about while folks feeling good.

There’s a saying that the minute you have a diversity director, you’ve failed. It’s incremental, but we have to be actually willing to change systems, not just the people. So many institutions started with good intentions, but the changes haven’t been where they should be. If you focus just on bringing students in now, in the moment, you’re not focusing on why these students haven’t been at your school to begin with. Yes, it’s imperative to think about teaching the students we have now, but we need to have the difficult conversations with ourselves. Have we institutionalized accountability? We started with the student community, and then professional development for adults, but we never talked about how we grade, what we grade, and why we grade. We were never talking about advancement, admissions, communications, or the business office. Those systems are what maintain white supremacy in a school. They will sustain themselves if we don’t create systems of accountability. We may also need to start reimagining what schools could look like, and maybe even why independent schools exist.

I did a Masters’ with Klingenstein (at Columbia). In one school, we were asked: “Should independent schools exist?” I basically said that I wouldn’t engage with the question. Looking at Audre Lorde’s challenge: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” The minute you ask, you’re concerned with the school, not the system, not the implications of the system. Independent schools exist. Period. Let’s not have the conversation. Let’s talk about how they exist, and how we need to reshape that. My thesis was basically: “occupy independent schools.” We have people in them who recognize the need for justice, so let’s capture this moment, put people in the right positions, so that instead of this being a system for white, wealthy, (especially males), how can we capture that power to feed our national and international opportunities for change?

What do you make of schools’ responses to @blackat accounts (during the spring and summer of 2020)?

I wanted people writing in to sue over the matters of injustice that they described. I know that seems extreme. But, hear me out. At this point, if schools don’t change policies and practice, it’s willful negligence. What are the conversations that we really need to have? Letters and promises not developed into actionable and accountable change are just another trauma to members of the BIPOC community. A lot of privileged and private institutions don’t take things seriously until they’re financially threatened, which is, I think, part of why legal redress is an option. There’s a creative force within schools, but to move forward, we need a community-centered approach that draws everyone in to make change. In order for that to happen, something has to drastically disrupt the current system. Possibility and liberation has to become the imperative over maintaining systems.

Productivity is a big part of white supremacist culture. We need to focus on slowing down, being creative, and really thinking through changes that need to be made, rather than just responding out of fear of what we’ve heard so far. We need to decenter whiteness. That means we have to think in new ways. If there weren’t limitations, what would we do? Let’s have creative conversations. Nicole Furlonge, the director at Klingenstein, talks a lot about listening on lots of different levels. As institutions, we’ve been talking so long that we sometimes don’t know what we could hear if we listened more.

What are some of the projects you’re working on, in and out of school, that feel especially present/urgent/exciting to you?

With Melissa Lawlor, who’s at Brewster Academy, I founded NISE (Network for Independent School Equity), which supports BIPOC and LGBTQ faculty at schools in Northern New England. We’ve run professional development about what it means to be at the margins when it comes to hiring. We meet up online — online life has helped. This community-centrism, beyond our communities, is important — we want to create interconnection for adults, rather than the heightened sense of disconnection or stuck in schools feeling you can get.

Melissa and I also consult with Athletic Directors and departments. In schools where we value competition, there’s a real place to make change in sports. If we can get all these athletic directors talking about bias and how it shows up, and have them work through scenarios that they haven’t recognized before, they can carry that to their coaches. Regardless of what you think about athletics culture, there’s so much that you can do there. We’re thinking about moving that into collegiate athletics, too. That area is really ripe for this type of learning.

I’m also doing some work with BB&N’s alumni executive council on what it looks like to model an anti-racist framework at a board level. In that, there’s anti-racist white community learning which has to take place in order for us to reimagine what boards could look like and be models of in independent schools. Milyna Phillips who championed this work has a model that could very well change this in many schools. Other places should be looking to their commitment and her work to move them forward.

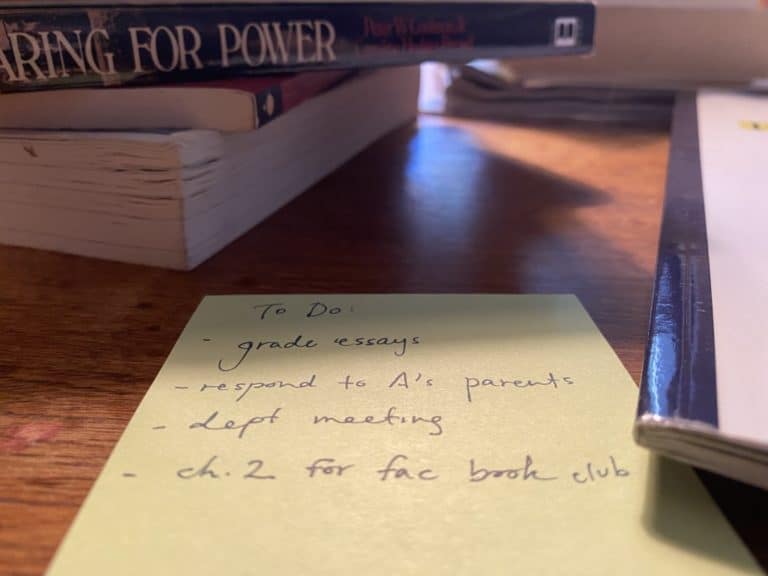

At Holderness, this is a hard year to do this work at a school, especially a boarding school, because we’re so scheduled. The piece we often miss in this work is that the foundation of it is socio-emotional intelligence and development. Because of Covid, we changed our schedule, the one thing that independent schools never change. But we could! So, on Saturdays we have non-academic classes, and one of them is with our counselor and chaplain, one with my team, one is outdoors / service-learning, and one is grade-specific. For me, being able to institutionalize a time where these conversations are possible has been huge. I have really good support from my Head of School, and over the summer, twenty of us were involved in doing an audit for the school, and we used an anti-racist framework for every meeting. Using the four levels of anti-racism, I’ve developed a model for the meetings that takes away the idea that we just enter, are productive, and then leave. So we have a list of recommendations for Holderness that will probably take us years, but they’re things that are good, that work.

We’re doing a curriculum review, but when I talk about curriculum, I’m not just talking about content. We’re also looking at cultural competency, how you create community, and so there are a number of aspects of what that looks like. As a school, just to get that data, rather than trying to judge it, let’s figure out where we are. The other thing that’s a part of the curriculum review is pedagogy. In independent schools, not everyone has an education degree. How we teach varies and can foster, support, and erode the aims of a diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice initiative.

We focus on growing and enhancing the practice of educators as they implement student-led discussion in the classroom. Where do you see discussion working and where do you see it needing to grow and evolve in schools right now?

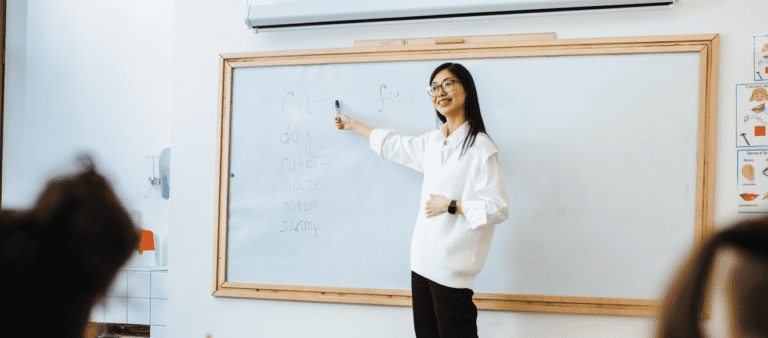

In Zaretta Hammond’s Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, she talks about the different levels of the brain. The neocortex, where you learn, is the third. You have to feel safe and comfortable being uncomfortable; if you don’t get to those things, learning doesn’t happen, or it’s really painful. We think about instructional design, and specifically pedagogy, conversations are where we make connections. I could have all kinds of representation up in my room, but the way that I talk to them, and the conversations we have, matter. We often think about History and English, but the way we structure and create opportunities for conversation across all disciplines is the way that we teach what it means to listen and what it means to build a relationship where information can be explored. In my mind, then, conversation is one of those foundational pieces. The way I talk to kids when we come in the room matters. If I’m talking to one kid about football, do other kids feel left out? Conversations are what make us human. In a math classroom, how you put up a problem is a conversation. Outcomes: when we think about outcomes, sometimes I think we go to skills, as opposed to habits of being and ways of being. Conversation’s a big part of this.

We’ve heard it forever that we’re teaching kids for jobs that don’t exist. The way we have conversations, grounding that in listening and curiosity presents the possibility for creativity. If our outcomes are skill-based and product-based, then what are we really teaching students? We’re teaching them that there’s an endpoint to education. Thinking about conversation and the outcomes that we want students to learn — at Holderness,we often say “who do we want the student to be who walks across the stage?” — and that’s different from asking what we want them to know. What are they really going to need? The habits of being and the ways of thinking. Conversation is imperative.

How can teachers foster creative and open-ended conversation that enhances equity and inclusion in the classroom?

I started using a growth mindset rubric a few years ago. If you can understand what it means to monitor your own struggles, then the skills are going to come. When I give this to students and restructure my classroom so that this is what it’s about, that it’s about taking risks and not trying to be right, but to learn, they’re so confused. They’re like, wait, what do you want us to do?

One of the key things, too, is reflection. We undervalue slowing down and reflecting on what we’ve done, how we’ve done it, why we’ve done it. The parents are always wondering “you’re using this rubric, but what are they doing in English?” My experience in school was always about getting the grade and passing the standardized test. This idea of kids changing their minds — there’s so much that we don’t know in the world. Helping students understand that and be comfortable with not knowing is hard, in part, because we assess with grades. A lot of schools have gone to competencies, and I believe in that. Grades are an abstract thing that doesn’t tell a kid a whole lot, but it’s a lot faster than writing feedback or having a meeting. That’s a conversation that we don’t have a lot. Assessment is a conversation. But are we involved in it? Are we aware of what we’re communicating? Are we having conversations that are embedded in curiosity and care and creativity? Because of the culture we live in, because a grade has to be there and it’s a way for people who don’t know you to make decisions about your future, we aren’t, always. I get it that kids just want the answer. They have all those external pressures coming from these numbers and letters that we assign that hold no value in your life beyond college. It’s this terrible systemic conversation we have that teaches young people to value themselves in ways that aren’t fruitful for our hopes for what the world will be or become.

We can work on being in conversation about the work that students do. One of the things I’ve been trying to get my students to realize is that every class is feedback; they only know feedback as grade-getting. This idea that I’m giving you feedback when I respond to a question in class, restructure something because we need to change at the moment, and so on, is also a form of feedback. I also like to tell them when I change lesson plans. I structure and plan, but I also want them to see that I have a willingness to change based on the class’s needs.

With the 9th graders, I try to always have one-on-ones with all of my students at least a couple of times a year. We sit down and talk about what they’re working on. There’s obviously power at play in a classroom; decentering the teacher in a classroom is really, really hard. For them to recognize that someone who they see above them with power, like a teacher, is someone who they can have a conversation with — that they can develop a relationship with someone — and that it can be fun, that matters to me.

What’s one prediction you have for the future of education?

There is a part of me that wants to be hopeful in response to this. There is also a part of me that is a realist. In the opening of Paulo Friere’s book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the introduction states:

Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

I continue to cling to the hope that the future of education is the latter. This imperative is not only integral but the only way to move towards liberation. And in order to do so, we must create a union of creative and critical listening, thought, and dialogue.