Reading, Writing…and Talking: What if America Had a National Conversation Skills Curriculum?

In what feels like a divided, screenbound world, here’s something I think most Americans would agree on: we need to re-learn how to talk (and listen) to each other. How can we do that? One step would be to make the instruction of conversation skills a national priority.

Why? Discussion skills are democracy skills. They are workplace skills. They are relationship and wellbeing skills. And our citizens – particularly, our children and young adults – don’t have them.

Conversation is how democracy, work, school, and life happen.

Several recent studies have brought this national conversation crisis into sharp relief, both in terms of what a communication skills deficit means for individual lives and broader society.

At an individual level, conversation is how humans connect with each other – it’s how we feel seen, heard, trusted, and loved. Today’s headlines document a stunning sense of disconnectedness: increased sadness, hopelessness, alienation, and violence among youth, especially among adolescents who identify as girls and LGBTQ. Elsewhere, research on men and boys also documents increased alienation and decreasing pro-social behaviors. The Surgeon General’s two recent reports to the nation declare an “Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation” (2023) and a Youth Mental Health Crisis (2021). It is well-established that positive social relationships are essential for individual wellbeing…and every relationship begins – and over time deepens – with conversation.

More broadly, our conversation crisis has manifested in eye-watering political polarity. This bitter partisanship is not new, but fresh research has documented how it interferes with learning on college campuses and ultimately, decreases young adults’ faith in the power of communicating across differences. Their jadedness – and lack of ability and willingness to use conversation as a mechanism for compromise – is a fundamental threat to our democracy.

All of these studies corroborate the daily horrors we feel as we endure too-common tragedies: deaths by suicide, mass shootings, hate-filled outbursts in pedestrian digital spaces. We wonder how many of these could have been prevented by conversation – and we know it in our bones: our society is not alright.

A citizenry in crisis is a national concern, particularly when the very generation that should be a source of hope feels hopeless. It’s time for a national solution.

Here’s what I propose as a starting point: a national campaign for conversation that starts by teaching face-to-face discussion skills in school.

Why? Well, it sounds simple, but it starts with science. Conversation is a uniquely human capacity: monkeys and robots can communicate, but only humans can use conversation to interview grandpa, triage a patient, engage in democracy, fall in love, workshop the next great novel, negotiate a peace treaty, explore edges of faith and reason. Conversation gives meaning to individual lives; in aggregate, it defines democracy and history.

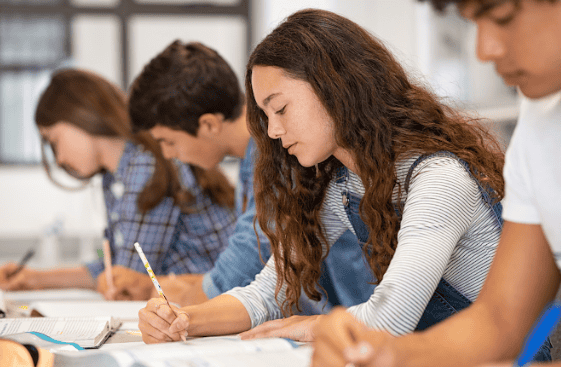

In our tech-centric world, conversation has become hard and scary – especially for kids. Screentime is not all bad, but it comes with a profound opportunity cost: children get less practice developing the in-person communication skills they need for nuanced conversation, whether academic or social. Yet, these skills – and the trusting relationships they build – are the best insurance policy against the pace, divisiveness, and infinity of digital life.

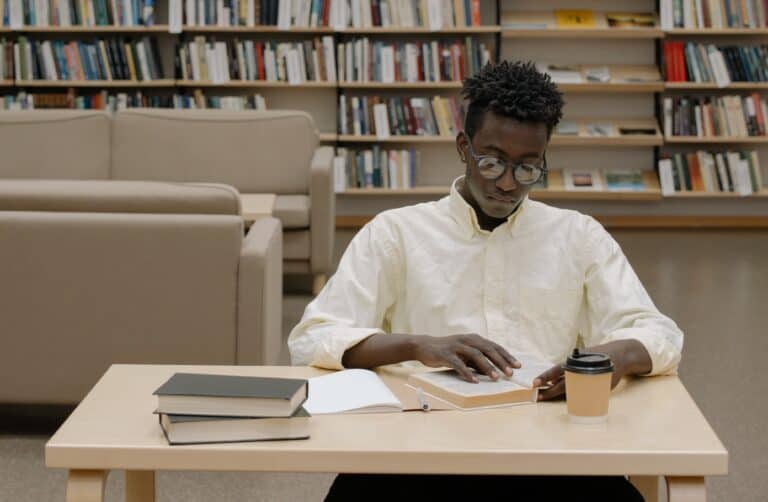

At R.E.A.L.®, we have proved that conversation skills are teachable – and learnable. For many children, school is the only place in their lives where they engage in screen-free conversations. Teachers then, are presented with an extraordinary opportunity: to teach the skills they need to build relationships, to share ideas, to listen to new perspectives, and to agree and disagree with respect.

So: what could a national campaign to teach conversation skills look like? I researched how other countries are tackling this challenge. It turns out there’s a pretty compelling example just across the pond . . .

Case Study from the UK: National Oracy Starts in Schools

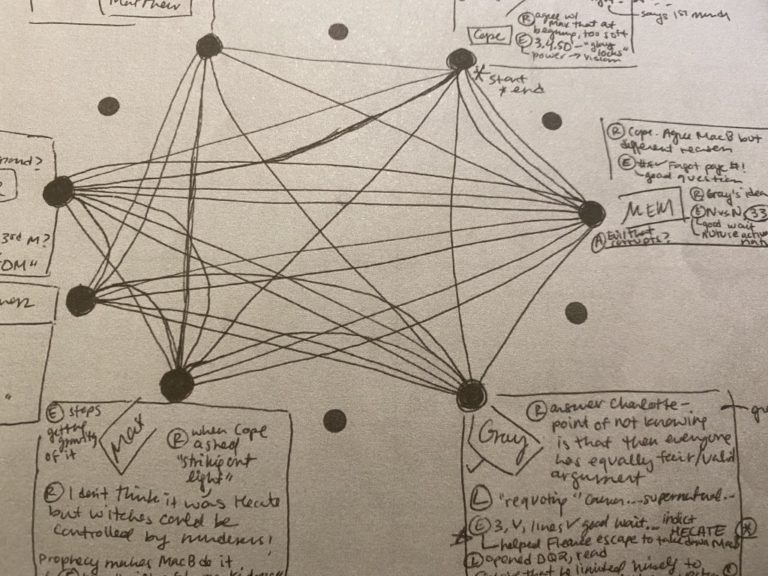

A campaign for what the Brits call oracy – verbal communication skills – is already underway in the UK. In 2021, an All-Party Parliamentary Group (the UK-equivalent of a governmental task force) commissioned “Speak For Change,” a study on the state of oracy in schools. It made a cross-party case for approaching oracy as a national concern and classroom instruction as a critical strategy for developing an engaged, healthy citizenry:

“Parliament is famous for being a place where talk matters – its name literally comes from the French ‘to talk’. Talk is the currency of politics – how we express our views, how we influence and persuade, how we negotiate and navigate disagreements and how we deliberate and come to decisions. But talk is also the currency of learning – how we develop and grow our ideas, understanding, thoughts and feelings and share them with others.

…The evidence [in this report] also showed how oracy’s long tail of benefits extends far beyond the school gates, improving young people’s chances of securing their preferred education and training pathway as they leave secondary school, and boosting their employment prospects. And we heard how oracy nourishes healthy debate, helps us bridge divides, navigate disagreement and understand different perspectives.”

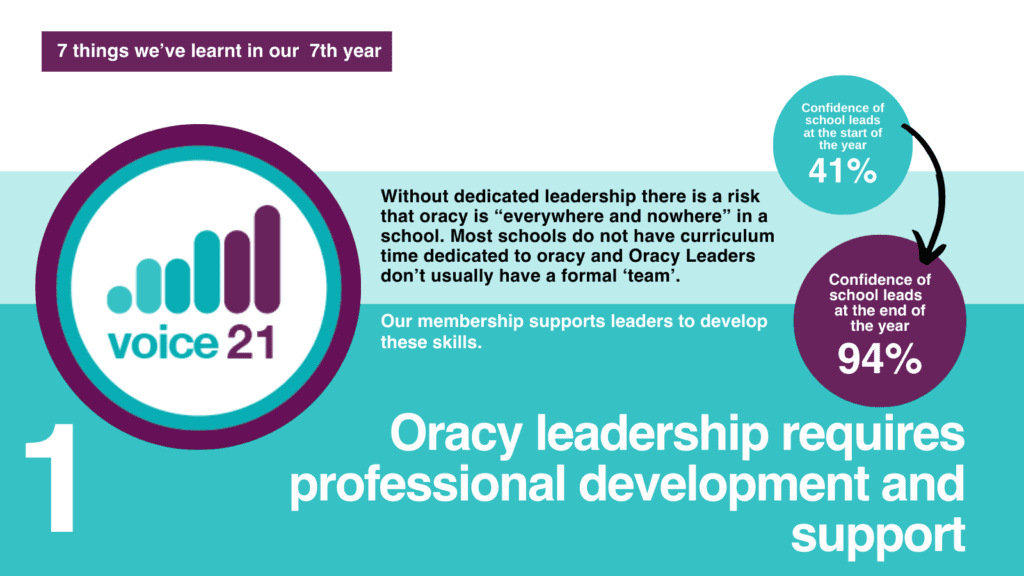

Beyond Parliament, several UK-based organizations are activating this work in schools. Best known is Voice 21, a national non-profit on a mission to promote oracy in schools.

To learn more about the UK’s campaign for conversation, I spoke with Victoria Anable, Voice 21 Chief Marketing Officer, to understand the organization’s vision for its national conversation campaign, why the team decided to start in schools, and what they’ve learned so far.

Q: Why focus on oracy skills in schools?

A: Spoken language skills are one of the strongest predictors of a child’s future life chances. On leaving school, children with poor verbal communication skills are less likely to find employment and more likely to suffer from mental health difficulties. Our research shows that oracy can improve outcomes across the following areas:

● Oracy increases engagement in learning, developing students who think critically, reason together and have the vocabulary to express their knowledge and understanding.

● Oracy fosters wellbeing and confidence, empowering students to build successful relationships and understand that their voice has value.

● Oracy equips students to thrive in civic life, as it helps students learn how to exercise their civic rights identities and listen to others’.

What’s more, oracy is one of the most cost effective interventions to improve learning outcomes, according to the Education Endowment Foundation. Oral language interventions demonstrate very high impact for very low cost, based on extensive evidence.

What is the state of oracy in schools? In the US, we technically have Speaking and Listening skills standards – do you already have national standards for speaking skills?

There are no official standards for oracy in the UK education system and only a minority of UK school shave consistent, coherent, or adequately resourced provisions to develop oracy skills in their students. That’s why we must campaign for oracy to have a higher status in the education system and promote the importance of oracy to the education sectors, schools, and teachers. Through our programmes, we empower schools to become oracy exports, transforming teacher practice and student outcomes.

We have launched an accreditation system to publicly recognize and accredit schools doing oracy work well. Voice 21 Oracy Schools that have succeeded in delivering a high-quality oracy education can become accredited as Oracy Centres of Excellence. We want all schools to become Centres of Excellence, prioritising oracy as equally important to literacy and numeracy.

To what extent have you collaborated with the government on these efforts, or do you plan to?

Voice 21 is the Secreteriat for the Oracy All Party Parliamentary Group, which includes MPs and members of the House of Lords from all political parties. In 2021, the APPG published its final report from the Speak for Change Inquiry, which highlighted the many benefits of oracy education and the detrimental impacts of a lack of provision for those that need it most. We welcomed the APPG’s calls for greater investment in teacher development for oracy and new non-statutory guidance from the Department for Education. We will continue to engage with the government and key stakeholders in the education sector to ensure that oracy is a national priority within education moving forward.

To what extent have you partnered with media to build national interest in the Oracy campaign?

Very much! We are proud and grateful for the extensive media coverage our efforts have received and the ongoing interest in our work. Two favorite examples: first, this BBC spot on the transformational effects of an oracy program at Bishop Young Academy in Yorkshire, in the north of England. Second, this SchoolsWeek article that clearly outlines for potential partners the multi-dimensional benefits of launching an oracy programme.

Most recently Alastair Campbell, right-hand man to former Prime Minister Tony Blair who is now a campaigner, podcaster and author, has given his support to our cause. He’s written articles about oracy in the New European and has spoken about our work on the UK’s most popular podcast, The Rest Is Politics. Having such a well-known and respected voice whose influence extends across UK politics and society has been hugely beneficial to our campaign. In his words, “oracy should take its place alongside literacy and numeracy in the staple diet of education”.

Even in an era when so many Brits disagree deeply on so much, stories like these give us a path forward, together.

We may be an ocean apart, but we in the US share so many of the challenges Victoria describes. The example of Voice21 and the UK’s national conversation about conversation is equal parts instructive and inspiring.

It’s time for the US to start our own campaign for conversation, for us to equip schools to teach American students communication skills they need for learning, relationship-building, and life in a democracy.